The pairing of poet Charles Bukowski and painter Walter Robinson is not as unconventional as it might seem at first. In his poetry and verse, Bukowski pulls no punches in his depictions of a life filled with drink, defeat and destruction. Robinson is known for his lushly painted and ironic critiques of mass culture, consumption and desire. This exhibition focuses on Robinson’s "Backpage Ads" and "Still Life" series, and complements them with Bukowski's poem "The Bluebird.” Through this dialogue each artist creates a context for the other’s work, and a new appreciation of Robinson's darker undertones is achieved.

Since the early 1980s Walter Robinson has been known for his creamy, gestural appropriations of pulp fiction and romance novel covers. From this retro illustrative starting point he has, over the years, gone on to critique the synthetic nature of American mass-market media through humorous images based largely on advertisements. From normcore fashion catalogs to fast food, Robinson has depicted the blandness of our dreams and shallowness of our desires by turning a mirror upon the ways we are told to think our lives should be lived.

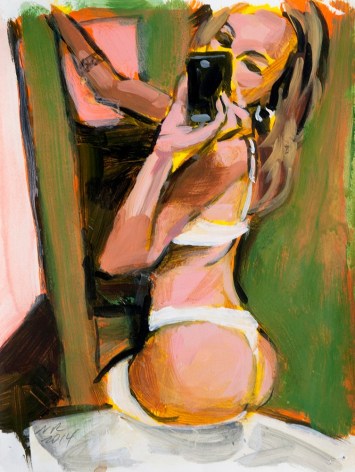

Robinson’s work is even more prescient than ever in this current age of selective Facebook posts and curated Instagram feeds. In the Selfie Era, the reality we are presented with is increasingly synthetic. An entirely new form of anxiety has been created, and we live in a world where our own lives have become a delivery platform for even more commercialization and consumption.

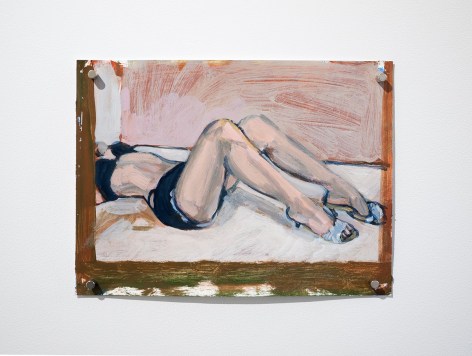

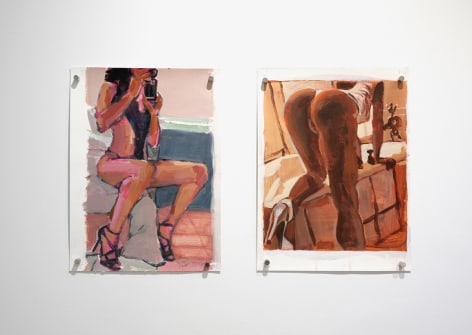

Robinson most clearly addresses these new notions of self-made reality in his Backpage series. Backpage ads are the photo-based ads in the back of Men’s magazines and certain newspapers, where escorts and massage girls promote their services. An old format, it has adapted to the times and now informs the “Casual Encounters” section of the Craigslist website, or profile photos on some Tinder dating accounts, to name but a few. In the Selfie Era, this format has developed an interesting dichotomy: if a girl’s face is visible, it often means that the ad uses a stock image, and the promise of the experience might vary greatly from the reality. If the face is blurred or obstructed, this often means that the image is a photo that the girl took of herself, implying that what you see is what you can expect. The notion of real vs. fake, both in terms of advertising and self-promotion, in an interesting one, and Robinson’s sketchy depictions are drenched in a range of emotions: excitement, despair, loneliness and vanity.

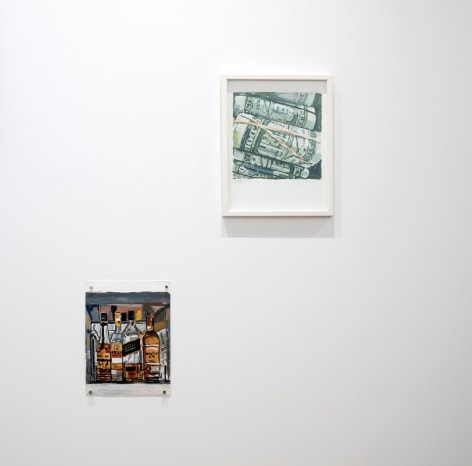

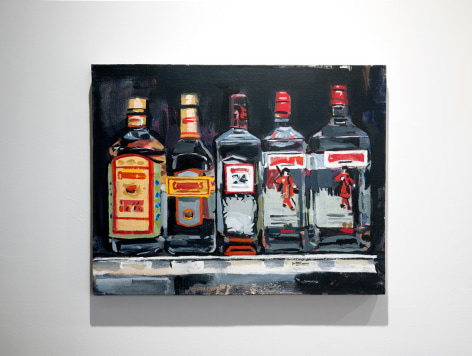

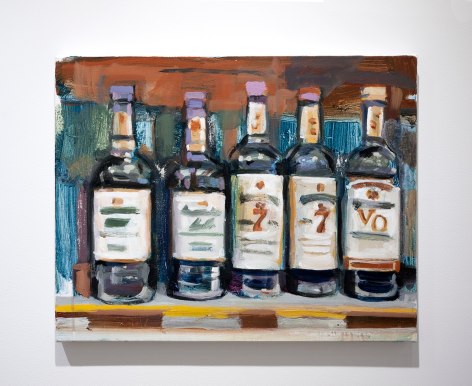

Just as the Backpage Ads posses the mental baggage of general moral odium, the accompanying Still Life works focus on the publicly acceptable objects of self-ruination. These are Bukowski’s old friends: the whisky bottles, beer bottles and cigarette packs that populate so much of his work. These objects can often be found in beautiful ads in popular magazines, but Robinson has isolated them and removed any of the lifestyle branding we are used to seeing. The still lifes paintings are often blurry and darker in tone than other ad-based artworks. Any notion of their benevolence, fun or benefit has been removed, and they now appear in a menacing light. This is where our inner-demons get their strength, and Bukowski gets his subject matter.

This is the heart of the pairing of Bukowski and Robinson. The paintings become illustrative of the poet’s world, and the poem helps us look at the paintings in a new way. We do not see them as flippant commentaries on our silly fantasy lives, but as direct and dark visions of the harsh realities of life.

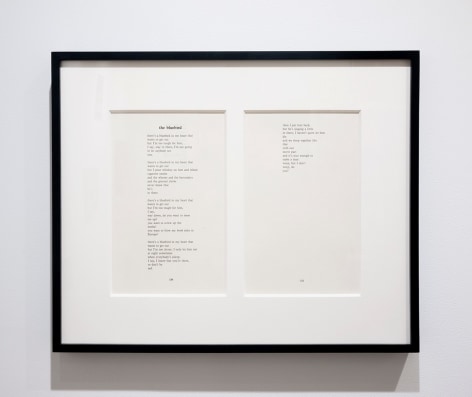

The central totem for the exhibition is a single poem by Charles Bukowski, “The Bluebird.” Bukowski was a poet and writer of unrestrained realism. His work reflected life as he lived it: excesses of alcohol in dive bars, surrounded by hookers, brawlers, bookies, the down and out. “The Bluebird” was first published in The Last Night Of The Earth Poems (Black Sparrow Press, 1992), and it contains many of the dark themes that were pivotal to the poet’s work. In the poem, Bukowski says that there is a bluebird in his heart that wants to get out, but he won’t let it. Though he cannot live without this last trace of decency and hope, he cruelly drowns the trapped bird in whisky and cigarette smoke. Sometimes, late at night, he will let the bird out of his chest, and talk to it. It is his secret, it is what keeps him going in a harsh world.

Both Bukowski and Robinson have worked in the other’s area of expertise before. Bukowski’s poems have been illustrated by other artists in the past, most notably Ken Price and Robert Crumb. Robinson has long been known as an intrepid art critic, starting with the co-founding of Art-Rite Magazine in the 1970s, and he has remained a prominent voice through to today. However, this exhibition brings something new to them both. This pairing is long overdue, and it is a pleasure to see their worlds intersect in such bleak beauty.