Uprising brings together two complementary aspects of German artist Björn Meyer-Ebrecht’s work. In both his ink-on-paper drawings and his painted-wood platforms one can see direct and indirect references to architectural history, sociology and the potential for interactions between art and the viewer.

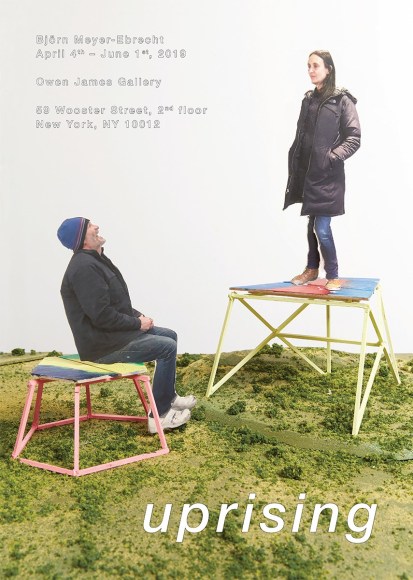

The structural platforms populate the gallery space, rising from the floor to varying heights. They are irregular in shape and brightly colored. The linear but loosely-brushed color stains that cover the flat top surfaces are offset by the monochromatic pastel colored support structures beneath. These objects hover between definitions, and their status is up for interpretation by the viewer. They can be walked around and observed in a room, like sculptures. They can be sat on while quietly contemplating Meyer-Ebrecht’s wall-mounted drawings. They can also be stood upon while loudly lamenting the current state of the world. To each his or her own.

The artist’s induction of playful interaction into his work shares a certain sensibility with previous contemporary artists such as Franz West. West’s covered couch and chair artworks especially could be seen as collections of social structures that promoted an actionable democratic aesthetic in art. Of course, Meyer-Ebrecht’s platforms are not technically furniture. They are forms, constructed and architectural, that lead the viewer to certain, open-ended engagements with art. In fact, the idea of ‘constructed environments’ created for the consumption of artworks has enjoyed a central role in the artist’s mind over many years. One can see this most clearly in his ‘Open Space’ and ‘Common Room’ projects during recent iterations of Bushwick Open Studios. In these cases, Meyer-Ebrecht created actual structures in his own studio that creatively (and generously) showcased works by other artist friends and collaborators.

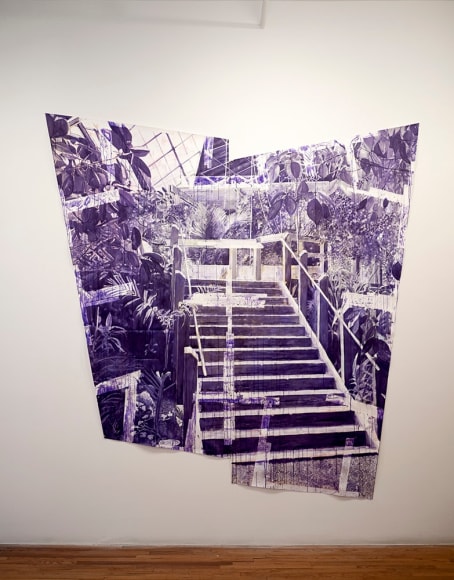

This sense of utopian social construction is embedded in the imagery of Björn Meyer-Ebrecht’s large format ink drawings. Constructed of irregular and angular shaped pieces of paper attached with clear tape, the imagery of the drawings are based on black and white photographs of mostly modernist, mid-century buildings. These anonymous locations reflect a range of motifs and emotions, from modernism’s banality (corporate offices, cafeterias) to its bizarre and controversial optimism (concrete public housing, playgrounds). For years these drawings were black and white, reflecting the documentary qualities of the source material they were based upon. However, recently Meyer-Ebrecht has used brilliantly colorful inks and depicted less obviously architectural settings. This switch moves the works away from the idea of the “past-tense” and instead confronts the viewer with an eclectic sense of “the present.”

The colored inks also breakup the hypnotic pull of the illusionary images, and so the viewers find themselves right where the artist wants them: somewhere between the sculpture and drawing, between color and construction, between flat and dimensional. The viewer becomes the central component of the works and installation itself.